Quotes from "Leading Through a Pandemic" by Michael Dowling and Charles Kenney of Northwell Health

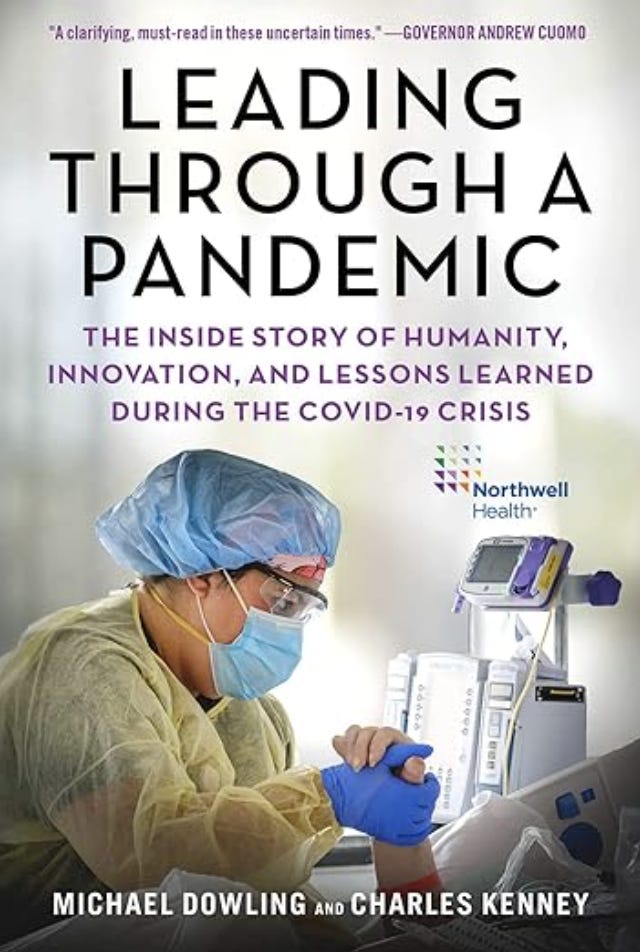

“Leading Through a Pandemic” was published by Skyhorse Publishing August 25, 2020. Michael Dowling was is the CEO of the Northwell Health system. Charles Kenney serves as “Chief Journalist at Northwell Health and Executive Editor of the Northwell Innovation Series.” It seems to me as if Kenney wrote most of the book.

Northwell Health was clearly the lead hospital system of the state of New York, partnered with them in many ways, in the manufactured “COVID” Holocaust. I told someone that once, and he asked me how I could back it up. I told him they had written a book about it. I hope he reads this.

There’s a lot of detailed information in the book for journalists and prosecutors to use. There will not be much of a summary here, just the quotes. I may refer back to this information and write more articles based on the information, and I hope other journalists do the same.

The quotes below are ones I chose to use, but I recommend that the reader obtain a copy and read the whole thing.

As background that can be used in conjunction with the informatin in the book, I’ve already written a few articles on “Cuomo’s death spike,” based on his press conferences, and I plan to do more.

The above are a pay articles, however I am making much of the original source information free however if you want to do your own research and write your own articles.

Below are complete transcripts of Governor Cuomo’s press conferences from January - May 2020.

Below that, the quotes from the Leading Through a Pandemic begin.

xiv

At Northwell, we tok care of more COVID-19 patients than any other health system in the United States. We nearly doubled our capacity of three thousand beds in a matter of weeks and that was barely enough. Our frontline workers saw illness and dath on a scale none had ever witnessed before.

xvii

At Northwell, we had advantages going into the crisis. One was size— twenty-three hospitals in the Greater New York area, eight hundred ambulatory sites, post-acute services, medical and nursing schools, a major institute for medical research, a core testing laboratory, nursing homes and home care, as well as a centrally organized transport system with a fleet of ambulances that allows us to move patients quickly and safely.

xvii

“Consider this scene that staff members faced each day, described by Dr. Lawrence Smith, Northwell physician in chief and dean of the Donald and Zucker School of Medicine.”

“In the hospital it is a very sad, stressful environment— almost surreal. I’ve been practicing medicine for a long time and I have never been in a hospital where (so many) patients are on ventilators completely sedated, completely paralyzed, not moving a muscle. Not a visitor in the entire hospital. Bodies lying bed to bed to bed, and the only noise in the room is the hum of the ventilators. And these patients never speak, never move, and yet they are all potential killers of the staff because they’re all shedding virus. I’ve been in ICUs and hospital wards for forty years now. I’e never seen what the inside of Long Island Jewish Hospital looks like right now, with just endless rows of bodies that are alive, but they don’t move and there’s nobody there to tell you about them. The staff has never heard these people even speak in most cases because the speaking ended when they arrived in the emergency room. It’s surreal. It’s frightening.”

xx

In May 2020, after the virus had passed the peak in New York, Governor Cuomo announced the Reimagining New York venture to plan for the new reality in a post-COVID world. He enlisted one of us— Michael Dowlng, CEO of Northwell— to lead the health care part of that initiative.

1

If you were searching for the epicenter of the COVID-19 virus in the United States, you would have to make your way to the borough of Queens in New York City, more specifically to 102-01 66th Road in the Forest Hills neighborhood. There you would find Ling Island Jewish Forest Hills Hospital, part of the Northwell Health system, where the virus unleashed its fury.

2

At a hospital a ten-minute drive from Forest Hills hospital, there was a dire warning of what was headed our way. A headline in the New York Times read: “13 Deaths in a Day: An ‘Apocalyptic’ Coronavirus Surge at a N.Y.C Hospital. The story focused on our Queens neighbor, Elmhurst Hospital, which is not part of our Northwell Health system but rather of the New York City public hospital system.

3

During a leadership meeting at our Forest Hills hospital in March, with the virus approaching, you could sense growing anxiety. The news from China and Italy was alarming. Team members engagend in emotionally-charged arguments about what we should do. At this poing Susan Browning, executive director of the hospital, interjected forcefully: “Guys, stop. We have a surge plan; we developed the surge plan when times were calm. We are going to take that surge plan our tright now and we’re going to talk from the surge plan. We are not going to make things up on the fly.”

4

And then came the onslaught, or tsunami, or whatever other metaphor you may chose for an overwhelming and unstoppable force. A deadly pathogen kicked down our doors and fought us for control of our hospital. As we said earlier, on an average day at Forest Hills, we see about 100 patients in our emergency department. At one point, there were 149 patients in our ED, 90 percent of them very sick COVID patients.

5

By no means was Forest Hills the only one of our hospitals under siege. Most of our entities faced comparable surges in patients including Long Island Jewish Medical Center in Queens, Long Island Jewish Valley Stream Hospital, North Shore University Hospital in Manhasset; and others. We were so inundated that we would wind up treating a full 60 percent of all COVID patient in the state of New York, more than anyone else.

6

On a typical day before COVID changed the world, Forest Hills might have one patient die. In one twenty-four-hour period in March 2020, the virus took the lives of seventeen souls in our hospital.

17

When our surveillance team saw the development of a new virus in Wuhan, China, in January 2020, we began putting our emergency operation together. Many people think of China as the other sie of the world, seven thousand miles from New York, but in our command center we think of it as a half-day plane ride. As we monitored from a distance, we pulled out the manual from our SARS experience that we had shared with the state and began to update contingency plans. We checked inventories and purchased additional supplies of PPE, ventilators, and other material. We acted absolutely as if it was happening, with complete dedication to getting as ready as we could get.

20

Part of our emergency preparedness includes a monitoring and early-warning capability. We watched events in Wuhan closely, and when it was clear the threat was growing, we sounded the alarm even before the sate government did, convening our team on January 21 in our emergency operations center in Great Neck, Long Island.

Then, suddenly and quite unexpectedy, our emergency operations command structure was disrupted. Weeks before the first confirmed cases, the verus stealthily arrived from Europe and penetrated the New York area in med-February.

22

Senior people in our organization had warned us about this type of virus and worse. Dr. Kevin Tracey, a neurosurgeon who heads our Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research at Northwell and who was intimately involved in all aspects of responding to the crisis, possessed a fascinating perspective based on his experiences during the SARS crisis. SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) first appeared in southern China in November 2002, spreading to twenty-six countries and infecting 8,098 people within months. The disease, which manifested in pneumonia or respiratory distress sydrome, was causd by a then-new coronavirus. it had a high mortality rate (nearly 10 percent) but a low rate of infection. A few months after SAS was first identified, in early 2003, Tracey was invited to a confidential meeting of a select number of senior scientists at the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), a division of the United States Department of Defense headquartered in Arlington, Virginia. Included in the meeting were Drs. Michael Callahan and Robert Kadlec, both of whom, along with Tracey, would play imortant roles in the coronavirus drama of 2020. The physicians were asked by the DARPA officials: “How should the federal government prepare for a virus with high mortality rates (10 percent or greater) and high infectivity.

After some deliberation that day and some calculations of a whiteboard, “we recommended establishing stockpiles of one to two million ventilators, PPE, and stockpilesof broad spectrum antibiotics and intravenous saline sufficient for ten to twenty million people,” Tracey said.

23

By February 2020, the news out of Italy was unsettling. Projections for our area were concerning, and then alarming. We accelerated our preparation and took a series of steps in anticipation of the virus’s arrival, and we did so well before we were mandated b the government to do anything. We:

(Editor’s note. I have chosen one item from a list of many items listed in the book:)

discharged any patients who could safely recuerate at home;

24

The result of these moves, in just a matter of days, was that our hospitals had fewer non-COVID patients than ever before— two thousand empty beds in a system where we typically run at, and sometimes just over, 100 percent capacity. On the eve of the outbreak, our hallways were quiet, many rooms empty.

30

We went from normalcy to battle stations, to converting virtually our entire ststem into the country’s largest COVID-focused health system, where our emergeny departments, medical surgical beds, and ICU beds were all packed with COVID-19 patients. Our hospitals had become COVID hospitals.

34

At the very early stages of the crisis, Governor Cuomo was pushing all health systems in the state to increase capacityby a minimum of 50 percent. He asked one of us (Michael Dowling) to team up with Ken Raske, head of the Greater New York Hospital Association, and to work with hospitals throughout the state to achieve that goal. In addition to that group, the governor asked us to coordinate actions with the major New York City systems including Mount Sinai, New York Presbyterian, NYU, Montehore, and Northwell. The leaders of those organizations would gather to confer on a conference call three times a week.

42

One of the ways we kept the numbers in our emergency departments and inpatient units under control is that we were able to see seventy thousand patients in our Northwell Health-GoHealth Urgent Care Centers and many more patients in our other ambulatory locations.

62

In February, Sendach and coleaguesjoined a call with hospital leadersin Italy when the Italians were going through hell: “They told us that it’s going to trickle and then, by the second week, it’s going to just overwhelm you.” They told us it’s not exclusively older people; that they were not sure why people crashed so suddenly.

64

On the calls to Italy, the Italian doctors had warned of potential harm from aerosolizing the virus. This was a serious problem for clinical staff in close contact with COVID patients. A clinician intubating a patients would pass a tube down the throat causing many patients to cough or gag, sending streams of virus into the air directly at the clinician. no matter how well gowned and masked workers were, this was a hostile environment. Once again, the engineering shop came to the rescue. There was a picture online from Taiwan of a Plexiglas box that looked like a square helmet that a Martian might wear. By placing it over the atients head, the clinician could then reach through arms holes and perform the intibation protected from the spray of virus. At North Shore, the idea of using such devices was proposed by Kelly Treacy, the nurse executive in charge of the operating rooms. Treacy proposed the idea on Monday, March 23. She discussed it with anesthesiologist Dr. Rich Grieco that day and the next. They engaged two outside vendors to design four prototypes. Early on Thursday, March 26, Treacy, Grieco, and a number of other clinicians reviewed the desing, offered a few modifications, and by Friday completed devices were arriving at the hospital.

66-67

At the peak, there were 715 COVID patients at North Shore, which made the hospital one of the largest COVID specialty facilities in the United States.

In mid-Apirl, north Shore had 150 COVID-positive patients inthe ICU on ventilators. Thse patients would end up staying for close to three weeks on average. Most would not make it.

67

On a Saturday in mid-April, Sendach joined in a North Shore celebration for the one thousandth COVID patient dischared from the hospital.

68

The celebration of the one thousandth discharged patient was a happy occasion for the ptients families, and staff. Ane when it took place, in mid-April, there was also a growing sense that the crisis was just beginning to ease in the New York area. On April 15, Sendach and Dr. Gitman wrote to North Shore staff:

We are seeing in increase in the number of patients going home and those who progress toward recovery.

69

The same weekend as the discharge ceremony, thirty patients at North Shore died from the virus.

75

It is no small irony that the products and supplies that would soon be desperately needed in the United States to protect clinicians from COVID-19 were actually manufactured in Wuhan, China, where it is believed the virus originated.

77.

The news out of Italy was terrifying. McCready and Donna Drummondd saw and read about frontline staff dying in some cases due to a lack of protective gear. A the same time, aware of the amount of travel between New York and various Italian cities, it was clear that the virus was on its way.

81

In New York State, early projections suggested that ventilators might well be in short supply at the peak of the pandemic. We purchased four hundred new vents and although we did not end up receiving all of them, we always had sufficient quantities, in large measuere because of our system’s ability to move equipment rapidly to wherever it was needed among our twenty-three hospitals.

89

Ideally, we wanted to standardize best practice treatments across the system for the simple reason that studies have shown that standardized care for certain conditions improves both outcomes and safety. The advisory group worked together to standardize care and provid clinical guidelines for frontline clinicians based on what they knew about respiratory care and what little data they had.

In May, the FDA approved the antiviral agent Remdesivir for use in patients with the virus. The problem was that Remdesivir was in relatively short supply. So our physician leaders defined a calculus guiding doctors on which patients would benefit most from it and which patients would likely not benefit. Based on the science involved, we established a tier system that prioritized patients whose conditions made them most likely to benefit from the drug.

92.

In general, we followed the Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrom Net protocol (ARDSnet), a NIH agreed-upon protocol for acute lung injury.

The differences in symptoms inand the rate and manner of disease progression made it hard to know exactly how to treate COVID patients. The lack of clarity was evident in a late March memorandum from physician leaders to doctors throughout our system:

The clinical advisory team is revising our clinical protocols on a daily basis as we gather infromatin shared by practitioners from arond the world. We remain committed to proceed based on available eviene, best common practice, and clinical judgment, and weighing known risks and benefits . . . (Editor’s note, break in text of memorandum is taken verbatum from the book) Despite all best efforts and attempts at consensus of optimal treatment strategies, the virus pahogenesis and mechanisms are still largely undefined, and we continue to have enormous challenges for patiens suffering and dying.

93

In the early stages of the pandemic, the reality, said Dr. Lawrence Smith, was:

that we knew literally nothing about it. The things that the disease did were continuous surprises. We also didn’t know the level of contagion. Certainly, when people got on a ventilator early on that was really a sign that they were very likely to not get out of the hospital alive.

94

Estabilshing standard best practices for treating COVID patients was difficult, because the disease was brand new and we kept learning as we went along. Thus, our standard practice, particularly for patients who deteriorated to the point where they required intubation, included specific vent settings, types of sedation used, and whether— and when— to perform a tracheotomy. We also turned patients over onto their stomachs (“proning”) to improve lung function.

97

No on had seen death rates this high. Throughout our system, doctors and nurses were having exceptionally difficult end-of-life conversations with families whose loved ones swere rapidly deteriorating on ventilators.

In many cases our doctors and nurses would connect with the family at home via FaceTime.

97

Dr. Lawrence Smith: They were on ventilators, stacked bed-to-bed in ICUs, paralyzed, sedated, never moved a muscle, never blinked, and had no relatives there to advocate for them. It became like a living morgue.

98

The most frustrating aspect of the crisis from a clinical perspective involved testing for the virus—or, more accurately, the inability to test on a broad basis. The word early on that came to Dr. Dwayne Breining, the head of Northwell laboratory, was that the FDA was taking a position that no tests from labs like ours would be approved because the CDC was setting up testing for the entire nation. THis meant that the major manufacturers of medical testes were barred from developoing and selling their own tests. When the CDC did release its test, it proved to be defective. This is a classic example of failing to prepare for a crisis. The virus was out there and it was coming to American—that was clear. Why wouldn’t we as a nation welcome large testing companies with excellent track records on other types of tests to market tens of millions of tests throughout the country? “I have no idea what the rationale for that was,” said Breining. “It makes no reasonable sense whatsoeverin terms of responding to the crisis. There was a lot of grumbling in the professional laboratory community in the US.” An online petition was signed by thousands of lab professionals with the message that, as Breining described it, “this restriction is unnecessarily delaying what is a true patient care need. And, based on that, I thing the FDA reversed course and then opened up this emergency us authorizaion pathway to allow laboratories to set up testing in their laboratories and develop their own tests, which also opened the door to the manufacturers at that time.”

99

In New York, we went to work on a test and collaborated on that effort with the team at the New York State lab that specializes in analysis and investigations related to threats to public health, and with whom we have a strong relationship. Governor Cuomo was instrumental in speeding up the process so we could begin working on developing what is known as a PCR test, which determines whether a person is infected withthe virus. We shared testing material and data with the state lab team and we were able to develop a test in our lab on March 8. The problem was that because it was a purely manual test, we could not produce the quantity needed to test our patients. “It’s not an automated test at all,“ Breining said, “so it requires basically some of my most highly skilled techs in the laboratory to run it, and basically occupies them for the whole time that they’re running it . . . and even then he most that could be produced were about seventy-five to eighty tests a day.” Soon thereafter we we able to improve with a semi-automated test and then finally in April, a fully automated test that enabled us to test two thousand people per day.

99

We also worked to make these tests more widely available to help communities determind the prevalence of the virus. … At the request of Governor Cuomo, we sent out teams into forty churches in Black Latino, and other communities where the population was disproportionately harmed by COVID. … Eventually, our lab developed the capacity to conduct more than seven thousand PCR tests per day…

101

An important moment came when all of the chief medical oficers from organizations involved with Javits— the Navy, the state, the New York City Department of Health, the Army, and the National Guard— gathered together and visited Lenox Hill Hospital in Manhattan, part of the Northwell system. Our doctors at Lenox Hill had fresh experience twith the disease and they explained that patients sick with COVID who were begining their recovery would be safe to move to Javits.

106

As we have noted, the key to all of the regulatory relief was a decision by Governor Cuomo to declare a state of emergency in New York, an action that triggered a series of emergency powers permitting him to suspend existing laws. The Albany Times Union reported that the governor changed 262 laws over a fifty-five-day period. In February, before the first case of COVID was discovered in New York State, the governor asked the legislatur to grant him broad authority to make whatever changes were necessary in the emergency to protect the health and lives of New Yorkers.

107

We worked together with the state, the Greater New York Hospital Association, and the Hospital Association of New York to inform officials that relief from existing rules wold better enable us to fight the virus.

108

by mid-March when the virus struck, scores of waivers each day would come in from local, state, and federal government, as well as from regulatory agencies such as hte New York Stated Department of Health, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, the CDC, and FDA. THe waivers and guidance covered everything from providing legal immunity to clinical staff in the hospitals to allowing recent graduates of medical and nursing schols to immediately practice in the hospital without gion g through the normal licensing process. In many cases, regulatory. restrictions that we and other health systems have strainged against for years were suspended, including elaborate certificate-of-need applications any time a health system wwishes to expand its footprint or services.

109

One of the most important rule changes— and we hope among the most sustainable— concerned telehealth. The New York State Department of Financial Services followed the lead of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, the federal ageny that administers Medicare, in saying that insurane plans should pay for telehealth visits at the same rate as they pay for in-person visits.

109

with a stroke of his pen Governor Cuomo allowed us to implement our surge plans, which enabled us to do exactly what he asked us o do— dramatically increase bed capacity. … “As long as you had enough oxygen and electricity to support the ventilators, you could use that space.”

112

We knew from firsthand experience that large numbers of our patients at Forest Hills Hospital, for example, were from low-income families in crowded urban neighborhoods.

113

At the governor’s request, one of us (Michael Dowling) has cochaired the last two commissions established to help solve the state’s Medicaid budget problem. There are ways in which we consider ourselves an extension of hte state government, and comfortably so. A number of our top executies worked for the state in various capacities. Some did so under the administration of Governor Mario Cuomo while others worked under more recent governors. Our Northwell state government veterans include Michael Dowling, Mark Solazzo, Head of Contracting Howard Gold, Communications Chief Terry Lynam, Chief Strategist Jeff Kraut, and Government Relations Head Dennis Whalen.

114

In New York, there is agood foundational relationship between the governor and leaders of major health systems. In the months ahead there will be discussions about how to create a state of overall readiness the next time that makes sure no one is left behind. These issues and many others are being explored by a number of leaders who have been asked by the governor to mhelp reimagine the future of New York post-COVID. Among those involved in this initiative is Eric Schmidt, former CEO of Google, along with Mike Bloomberg and the Gates Foundation. In addition, one of us (Michael Dowling) was asked by the governor to help reimagine the future of health-care delivery in the state.

118

Having been ivolved in scores of trials through the years and authoring more than 350 research papers, Tracey was well-known throughout the pharmaceutical world. On Saturday morning, March 14, he reached out to scientists he knew at the biopharmacueutical companies on the forefront of COVID, research, Regeneron and Gilead. … Teams from Regeneron, Northwell, and the FDA worked through that March weekend and by Monday Tracey and colleagues were reviewing a research protocol. The review process of setting up a clinical trial and treating the first patient normally takes two or three months. In this instance the Northwell and Regeneron teams had done it in three days.

119

On the Regeneron trial at Northwell we enrolled 216 patients in a few weeks thanks to the work of the COVID clinical trials unit and the principal investigator, Negin Hajizadeh. … The trial was barely a few weeks old when, suddenly in early April, Regeneron froze the initiative. The company was reviewing daa from the first wave of the trial and amining to reopen it with a larger group. But the data, said Tracey, was disappointing. The remedy was not working in early-stage patients, causing Regeneron to switch gears and focus the trial on the very sickest patients.

119

Tracey, along with coleagues Dr.s Marcia Epstein and Prasat Malhotra, also worked with Gilead Sciences on a trial for the drug Remdesivir. … He was emphatic with Gilead, as he had been with Regeneron, that they would do the trials on one condition: “Our patients are dying, and I need you to tell me you are going to send me as much drug as I can use.” … Regeneron had followed through on this commitment, but Gilead never sent more than a few doses at a time, frustrating Tracey and his team.

121-122

During the week of March 17, while working on both the Regeneron and Gilead trials, Tracey received a call from a physician colleague he had known for twenty-plus years. Dr. Michael Callahan, who had been at the meeting Dr. Tracey attended twenty years earlier advising defense department officials about preparing for a pandemic, and who was in China during the coronavirus outbreak, told Tracey that there was some important data that might hold a clue for a new trial. It seemed that patients in China who had been diagnosed with acid reflux (heartburn) fared far better when infected by the virus than others. What was different about these paiens was that al were taking famotidine for their reflux disease, an over-the-counte drug sold under a variety of brand names, including Pepcid.

Dr. Callahan said he understood that we at Northwell were getting “slammed” by the pandemic and Dr. Tracey explained that we had many people dying in our hospitals and no proven therapies with which to treat them. Callahan explained what the data in China showed about patients on famotidine. He added that computer modeling indicates it was possible famotidine interacts with of one of the virus proteins and while they didn’t know if that would kill the virus, a study was reasonable. The COVID clinical trials unit went to work setting up the trial.

At HHS, Robert Kadlec, assistant secretary for preparedness and response at the US Department of Health & Human Services, asked Tracey to move quickly to conduct a research study into the efficacy of famotidine as a therapy for COVID-19. The trial, led by principal investigator Joseph Consigliaro, commenced on April 7 after Northwell quietly purchased a significant supplyof the drug. This took time in light of the fact that the trial required and injectable from of famotidine, whichis rarely used, so that hospitalized patients could be given the drug intravenously. The study was funded by a contract from the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA).

Tracey was pleased to have the study up and running, but it was not exactly an ideal study in his view. Politics had interfered with the shape of the trial. President Trump’s insistent promotion of hydroxychloroquine as a remedy had influenced patients and doctors to demand the drug. This was an unfortunate situation. There was no scientific evidence that hydroxychloroquine could work but the president had been promoting it nonetheless. Worse still, a later study on hydroxychloroquine in April was halted when it ws learned that some patients had developed irregualr hear rhythm while on he drug. Nonetheless, at the time the famotidine trials began, hydroxychloroquine had suddenly become the current “standard of care” and therefore had to be tested along with famotidine.

123

As Tracey put it, “the standard of care was determined by politics.” Then suddenly, in the midst of the trial of hydroxychloroquine with and with out famotidine, hydroxychloroquine was judged to no longer be the “standard of cae.” The new standard would be Remdesivir, based on comments by Anthony Fauci that it had demonstrated some clinical value.

126

“We saw this huge spike, with a stealth-like nature this thin g running wild very quickly, the case count skyrocketing,” said Soro.

Fear was sparked, he said, “by the insidious nature of COVID, the spped and stealth with whih it strikes. And we saw it very early on. Nobody knew how they were getting it.”

136-137

Observed Dr. Kevn Tracey:

There will be another emerging disease with the potential to do even more damage than this coronavirus did. If the coronavirus was a seventy-five-year flood, we need to be prepared for the thousand-year flood.

Saying it wouldn’t hapen again is like saying we’re never going to have another hurricane or another tornado or a sudden flood. … For instance, why didn’t Ebola spread much more far and wide than it did? Because of effective clamping down on identification of cases and isolation. And we learned from this event that all the draconian measures we put in place with closing things down and social distancing did flatten the curve. … But if if happens with a virus that’s much more lethal, we’re going to have to do it much better and much faster.

137

And we should never again have less than a robus stockpile of ventilators and other essential equipment.

139

Among the most important lessons of our experience in this pandmic is that regulatory flexibillity promotes speed, creativity, and efficiency— and saves lives. When the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, the Food and Drug Administration, and state regulatory agencies waived rules, they demonstrated the potential flor a new age of innovation in health care.

140

Poorer communities in New York and elsewhwere were disproportionately harmed by the virus. … The greater likihood that poor people as well as from miniority populations will die from the virus presents further evidence of a health divide within American society.

141

Also, physician leades at Northwell collaborated with faculty at the State University of New York at Albany to study the impact of COVID on minority communities throughout the state.

148

The COVID crisis was an unfortunate but nonetheless remarkable opportunity to spread the use of telehealth in he United States beyond what would have seemed possible just months ago.

149

Before the crisis, the use of telehealth by our physicians was at only a modest level, but when the crisis struck, telehealth use spike in a way we have never before experienced. … On February 28, we were averaging about 250 visits a month on our telehealth platform called American Well. On May 2, we had 3500 and on May 4, we had 6400.

156

Nicole Fishman, RN, is a nurse manager at Huntington Hospital.

“One thing I’ve been surprised about is that younger patients— people in their forties, fifties, and sixties, are deteriorating faster than I would have anticipated.”

157

Else Inapa is a nurse prctitioner in North Shore University Hospital’s intensieve Care unit.

“The unit I work in is a COVID quarantine unit, the highest acuity and sickest patients we have in the health system. THe patients’ average age is in the fifties, but we have people who are in their twenties, thirties, forties, and fifties— much younger than we anticipated.

In the intensive care unit, one of the many now throughout the hospital, we are using ventilators to help patients gen enough oxygen. Under normal circumstances, not all ICU patients are on a vent. But right now, with COVID-19, everyone in the ICU is on a breathing machine. This oxygen is helping them survive.

161-162

Elisa Vicari, LCSW, is a social worker in the Intensive Care unit at North Shore University Hospital.

As a social worker in the Intensive Care Unit at North Shore University Hospital, I’ve become immune to people passing away. Death is an unfortunate part of the job because we are treating the sickest patients. …

During the patient surge in late March, we were caring for otherwise healthy twenty- and thirty-year-olds who were unaware of their surroundings and had no business being intubated. These are previously independent individuals who have been abruptly put on life support. …

Adding to the complexities of this situation, visitation was resricted, and patients in our unit were unable to speak to their families. …

In the ICU, patients are mostly intubated. Finding close connections has been chalenging. Instead, we have grown closer to families, FaceTiming with them every other day for status updates, learning nicknames and favorite songs, and hearing about their pets who await them at home. …

In some end-of-life circumstances, visitors have been allowed to see their loved ones in their final moments.

163

The angel of environmental services: John Baez works in the Environmental Services Department of Staten island university Hospital.

When the crisis was at its peak, I remember seeing one case after the other. People begin for their lie, “I can’t breathe, I can’t breath.”

END

No comments:

Post a Comment